The ancient debate between Zhuangzi and Huizi on the bridge over the Hao River remains one of the most profound explorations of epistemology in Chinese philosophy. Known as the "Hao Liang Debate" or the "Fish Happiness Debate," this dialogue transcends time, challenging modern readers to reconsider the boundaries of human cognition and intersubjective understanding. At its core, the exchange questions whether we can ever truly know the inner experiences of another being—be it a fish, another person, or even the universe itself.

On that fateful day, Zhuangzi observed fish swimming freely in the river and remarked, "The fish are enjoying themselves." Huizi, ever the logician, countered: "You are not a fish—how do you know the fish are happy?" Zhuangzi's retort—"You are not me—how do you know I don't know the fish are happy?"—unleashed an epistemological labyrinth that continues to resonate. This wasn't merely wordplay but a radical inquiry into perception: Can joy (or any subjective experience) be measured objectively? Is empathy a bridge between consciousnesses or merely an illusion of projection?

The debate exposes a fundamental rift between rationalist and intuitive approaches to knowledge. Huizi represents the analytical mind, demanding empirical evidence for claims about others' experiences. His position foreshadows modern skepticism—how can we verify qualia (subjective experiences) when we're trapped within our own nervous systems? Zhuangzi, meanwhile, embodies phenomenological trust; his epistemology leans on direct apprehension of the world's interconnectedness. When he later says, "Let's go back to your original question—you asked me how I knew the fish's happiness, which means you already accepted that I knew it," he highlights how language itself presupposes shared understanding.

Contemporary cognitive science adds fascinating layers to this 2,300-year-old conversation. Mirror neuron research suggests we're wired to simulate others' states, while studies on "theory of mind" reveal how humans instinctively model others' perspectives. Yet these biological mechanisms don't fully resolve Zhuangzi's challenge—they merely describe how we project understanding, not whether such projections correspond to reality. The "other minds problem" in Western philosophy echoes Huizi's skepticism: all we ever perceive are behaviors, never experiences themselves.

Eastern and Western thought diverge intriguingly here. While Descartes' "cogito" anchors truth in individual consciousness, Zhuangzi implies knowledge arises through relational harmony. His famous butterfly dream—wondering whether he was a man dreaming of being a butterfly or vice versa—extends the fish debate's themes: if boundaries between self and world are fluid, then perhaps "knowing" requires participation rather than detached analysis. This resonates with quantum physics' observer effect, where the act of measurement alters the measured phenomenon.

Applied to modern AI ethics, the Hao Liang Debate becomes alarmingly relevant. When we attribute emotions to chatbots or assume animal consciousness in lab experiments, we replay Zhuangzi and Huizi's roles. Corporations now claim their algorithms "understand" user needs—but is this marketing empathy or genuine cognition? The fish debate cautions against both anthropomorphic arrogance (assuming we can fully know other entities) and solipsistic nihilism (denying all possibility of connection).

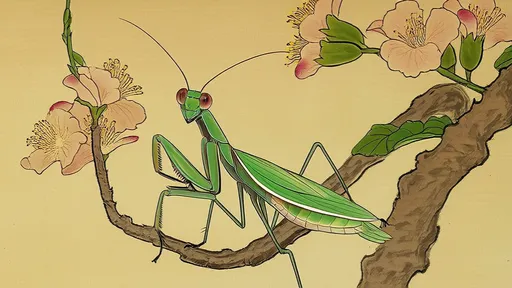

Artistic interpretations across centuries reveal how this dialogue morphs with cultural priorities. Song Dynasty painters depicted the scene with Zhuangzi leaning precariously over the water—a visual metaphor for epistemological risk-taking. Contemporary installations like Xu Bing's "Background Story" series literalize the gap between perception and reality, using backlit shadows to echo Zhuangzi's insistence that reality may be inverted from appearances. Even in Borges' short story "The Garden of Forking Paths," the Argentine writer channels Zhuangzi's perspectival relativism.

Perhaps the debate's greatest lesson lies in its irresolution. Unlike Western philosophical traditions that prize definitive conclusions, Zhuangzi and Huizi leave the question vibrating in the air like a plucked zither string. Their exchange models what psychologist Carl Rogers called "dialectical tension"—the creative friction between opposing truths. In an era of polarized certainties, the fish happiness debate reminds us that some questions aren't meant to be answered but inhabited, their ambiguity expanding our capacity for wonder.

As climate change forces humans to reconsider our relationship with non-human consciousness—from coral reefs to AI—Zhuangzi's playful humility offers a radical alternative to Cartesian domination. If we cannot definitively prove a fish's joy but cannot disprove it either, then ethical action must proceed from what Buddhist philosophy calls "don't-know mind." The bridge over the Hao River, it turns out, wasn't just a setting for debate but the debate itself—a span between knowing and not-knowing, forever inviting us to walk its length.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025